How to start training core compression strength.

If you're an adult gymnastics skills seeker that wants to improve movements like L-sits, toes-to-bar, skin the cats, pistol squats, press the handstand and overall gymnastic skills, then core compression strength is going to be essential.

The good news is you're in the right place now.

In a previous post, I wrote about how to start training pike flexibility. In it, I spoke about stretching the posterior chain muscles, and I also talked about building an understanding and awareness of anterior pelvic tilt (APT) and posterior pelvic tilt (PPT).

I also shared several great exercises that you can use to start training pike flexibility.

Now, why I'm mentioning this and what pike flexibility has to do with core compression strength? They support each other, and you need good pike flexibility to train core compression strength effectively.

When I first started training forward fold flexibility - pikes and pancakes - I was working towards my goals of the press to handstand. I could do one repetition of a press to handstand, but there was no way I could link multiple repetitions or progress to a stalder press.

I needed flexibility, and no amount of strength training would ever help me unlock these movements.

It's still an ongoing journey, and I'm getting closer to the stalder press and multiple repetitions of the press to handstand. I've made excellent progress with my flexibility, but there's still work to be done.

This is where I found specific core compression strength training helpful.

Whenever we stretch a muscle on one side of a joint, we shorten the muscle on the opposite side.

Let's take the ankle as an example.

When stretching the calf muscle, we dorsiflexion the ankle. The calf muscle is lengthening, and the tibialis anterior - the shin muscle- is shortening.

We can hang out passively in that stretch or actively contract the tibialis anterior to pull the ankle into a greater range of dorsiflexion and increase the stretch on the calf.

This same principle applies to every joint and muscle we are stretching, and it also applies on a more global level when we're stretching something like the pike.

When we are stretching the muscles of the posterior chain (calf, hamstrings, glutes, spinal erectors, etc.), we can forcefully contract the muscle of the anterior chain (tibialis anterior, the quads, the deep hip flexes, and the lower abdominals) to pull us deeper into the stretch.

The more we can shorten the anterior chain, the greater the stretch will be on the posterior chain.

The shortening of the anterior chain muscles is known as core compression in gymnastics, strength and flexibility training.

But here's the catch.

If you've got a very tight posterior chain, it will limit your ability to contract the anterior chain. The anterior chain muscles are fighting against the tension that you have in the posterior chain, making it a lot harder to shorten the anterior chain muscles and close that angle between the torso and the legs.

One common reason we see gymnastics skill seekers struggling to train movements like L-sits, toes-to-bar, skin the cats, pistol squats, and press to handstand. They must bend their knees to perform the exercise, which doesn't help increase core compression strength or make the movement look pretty.

They can't perform the movement with the correct technique because the posterior chain muscles are tight, and the anterior chain muscles are weak.

There are some people, let's take yogis as an example, who are very flexible. They spend a lot of time stretching the muscles to fold into a pike easily. But they often have hip or lower pain because they don't have the strength and stability around the hip muscles.

Even though they have a high level of flexibility, they lack the core compression strength and the strength of the other muscles to make the movement safe or even to start loading it.

Core Compression Strength & Forward Fold Flexibility Program

DOWNLOAD A FREE SKILL-BASED PROGRAM TO HELP YOU BUILD CORE COMPRESSION STRENGTH AND FORWARD FOLD FLEXIBILITY..

You don't just want to stretch the posterior chain to achieve the pike, you want to be able to strengthen those muscles and stretch and strengthen the anterior chain muscles.

So which comes first?

The anterior chain strength or the posterior chain length?

Well, it's a trick question because we want to train both simultaneously.

They work together, and they help each other. We can progressively build them up to support each other in our training.

I talk about stretching the posterior in the How to Start Pike Flexibility Training.

Many core compression tutorials suggest training seated leg lift variations to build core compression strength - this is seated pike single-leg or double-leg lifts.

Although these are great exercises for building core compression strength, you need to have a certain level of flexibility and core compression strength before you can start training these exercises successfully.

If, when you train these exercises, you need to lean the torso back so you can lift the legs off the floor, you're cheating the movement. And you're not training core compression strength effectively.

Remember, the goal with core compression is to close the angle between the torso and the legs. By leaning the torso back, you're opening that angle.

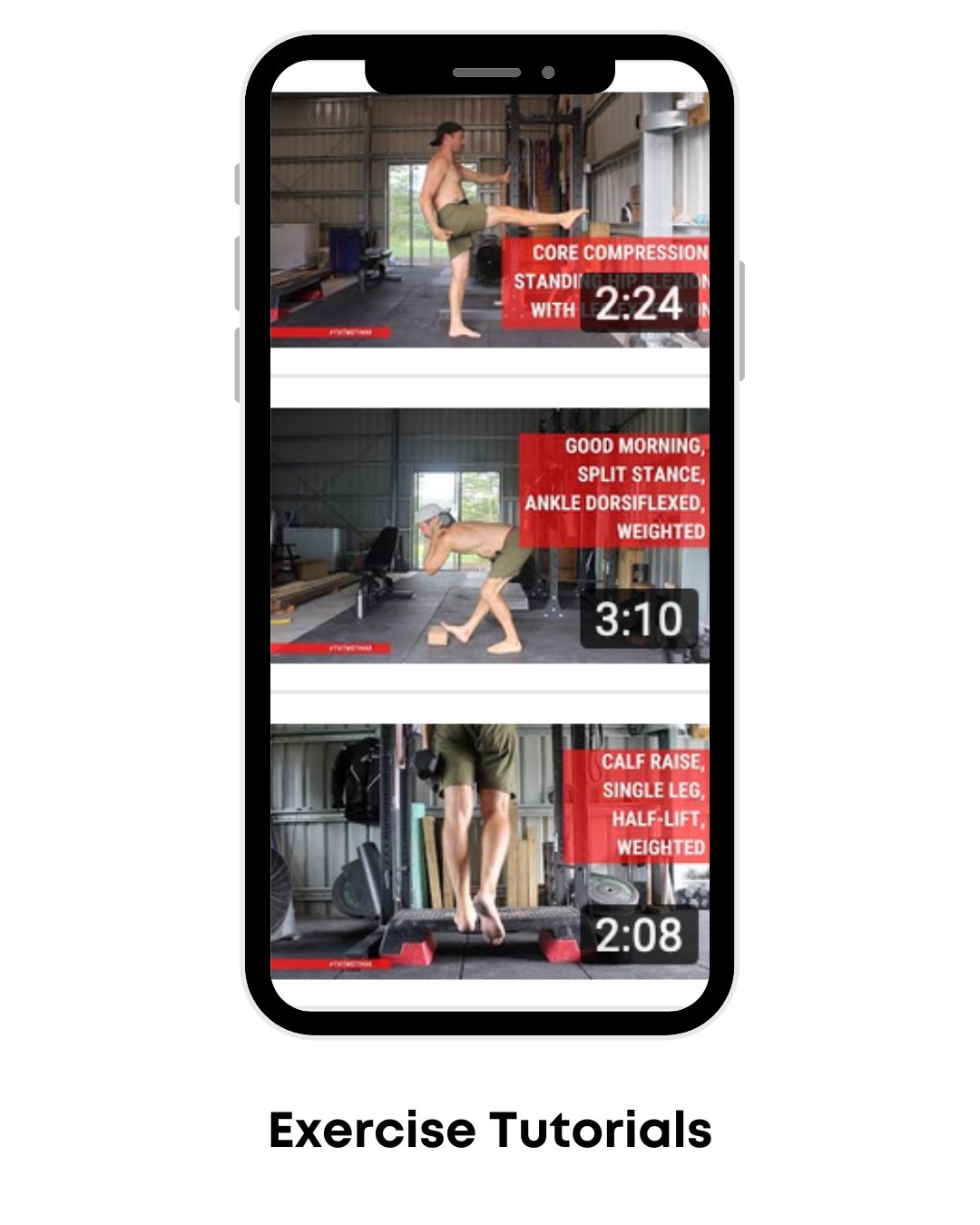

This is why I like to start with standing core compression strength training in a standing position, not a seated position.

Standing core compression exercises offer us a more accessible range of motion, and I find them far more effective for beginners.

It is important to note that in all the standing core compression variations I'm about to share with you, the goal is to keep the standing leg straight.

We tend to want to bend the knee of the standing leg because this allows us to lean the torso back, and it will enable us to cheat the movement, and as I mentioned above, this won't effectually train core compression strength.

Make sure you progress these movements in order and achieve each movement's milestones before progressing to the next movement.

With that said, let's take a look at the first progression.

I like to start with standing hip flexor, bent-knee lift-offs with the bent knee.

The bent-knee position shortens the lever length, which makes the movement easier. It's much easier to close the angle between the torso and the thigh with a bent knee.

Can you get the thigh to touch your belly? And can you hold this position for 30 seconds on each side?

If you can, then you're ready for the next progression.

Next up is the standing hip flexor with leg extensions.

The starting position is the same as before, but from here, we're going to extend the knee and straighten the leg.

When the knee is bent, we can flex the hip more and lift the leg higher. The bent-knee position helps lighten the load so we can contact the deep hip flexor muscles before we straighten the leg to increase the lever length and make the movement harder.

This can be a big step up from the bent knee progression. It can be helpful to start by doing reps and shorter holds. You might do five repetitions where you extend the leg and hold it straight for five seconds.

Gradually building up to five reps with 5-second holds on both legs. Once you can achieve this, we can do three repetitions with a 10-second hold, then two repetitions with a 15-second hold, and then build to one repetition with a 30-second hold.

If you can't keep both legs straight in the hold, you may need to return to the bent knee variation. If you find the bent knee variation easy, you can regress the leg extension by not straightening the leg all the way. Find a point you can hold for the specific number of reps and hold times. As strength improves, you can increase the lever length and progress to straightening both legs.

Gradually, you'll build the strength and the endurance to accomplish the milestone of holding both legs straight for 30 seconds.

Once you've nailed that, you can start training the standing hip flexor lift-offs.

Now, this movement looks very similar to the leg extension, but you're now going to keep the leg straight for the lift and the hold.

As I said before, it's much harder for us to lift the straight leg than to lift the bent knee. The advantage of the leg extension is allowing the hip flexes and abdominals to lift the bent knee and get into a good position before we straighten the leg.

Now in the standing hip flexor lift-off, the leg remains straight and the hip flexes, and the lower abdominals must work harder to lift the leg into position.

Again, we might use the same progression by performing 5 repetitions with a 5-second hold in each rep. Then progressing to 3 repetitions at 10-seconds, 2 repetitions at 15-seconds, and then being able to lift and hold for 30-seconds.

Again, we must keep the standing leg straight and not lean the torso back.

We're aiming to hold parallel or above with this.

If this is too hard, you may have to regress to the leg extension, or you can start by holding the leg below parallel and gradually working up to keep it parallel.

Once you've achieved the milestone of holding the legs straight for 30 seconds at parallel or above, then you should be ready to start training the seated leg lift variations.

Is there anything else besides standing core compression exercises?

Another excellent option for building core compression strength is hanging core compression exercises.

These also work well for beginners because of the accessible range of motion.

You can hang from a pull-up bar or a set of gymnastics rings, and you can build core compression strength by working through the following progressions.

I would start with the hanging tuck and focus on closing the angle between the torso and the thighs.

A nice tight tuck position.

You want about to hold this for 15 to 20 seconds before you progress to a single leg straight.

If this is a big step up from the tuck, you can play around with extending the leg. Over time you'll extend it further and further until you can hold the leg straight.

The leg must be parallel to the floor or above.

When we move to the single-leg straight progression, we want to build up to holding one leg straight for 15 to 20 seconds and then repeating on the opposite side.

From here we progress to the full L-sit. You can do this in a similar format to the standing core compression exercises.

You might do three repetitions with a 5-second hold in each repetition. Start in the hanging tuck, straighten the legs to a full L-sit for five seconds, and then move back to the tuck.

Once you can do 3 repetitions with a 5sec hold, you can progress to 2 repetitions with 10-second hold, and then 1 repetition holding 15- to 20-seconds.

Hanging core compression exercises can be more challenging than standing core compression exercises because you also require shoulder flexibility and grip strength.

Training Frequency

A mix of hanging L-sit variations and standing core compression exercises is a great way to build core compression strength.

If you're training core compression strength twice a week, you'll do standing variations on one day and hanging variations on another.

Training on the same day can often be too much volume for beginners so I wouldn't recommend it.

It's also helpful to superset core compression exercises with posterior chain flexibility exercises to speed up your progress. If you're looking for ideas, check out the How to Start Training Pike Flexibility post.

Remember, you want to lengthen the posterior chain because it will help you increase anterior chain (core compression) strength.

You also want to increase core compression strength to help you lengthen the posterior chain.

They both support each other.

So it makes sense to superset them together.

Summary

My advice is to take it slow. Work on the progression you are up to and superset your core compression strength with your pike flexibility.

I guarantee that you'll see progress.

And this is precisely what happened to online student Michael. In the beginning. He could hold a hanging tuck for 30 seconds, but when he tried to straighten one, he lacked both flexibility and strength.

Over the next 12 weeks, we focused on improving his pike flexibility and core compression strength. By the end of those 12 weeks, he could successfully hold a full hanging L-Sit for 15 seconds.

Much of what he did is covered in this post and the "how to start training pike flexibility” post.

If you want to work on increasing your core compression strength, stick to these progressions, just like Michael did.

If you're an adult gymnastic skill seeker that wants to build strength, increase flexibility, and unlock gymnastic skills that you never thought possible, sign up for my free weekly email.

Every Friday, I share gymnastics strength and flexibility training tips and give away a ton of helpful information. I link to videos, share blog posts, and let you know about new strength and flexibility training programs.

When you are ready to start unlocking gymnastics skills you never thought possible, add your email to the email list.

Happy core compression training.