How to increase Core Compression Strength

When we talk about core compression strength, we often think of movements such as seated leg lifts or hanging toes-to-bar. Both are core compression exercises, but they’re not the best starting place for building core compression strength.

So, where do you start?

What is core compression strength?

First off, let's make sure that we're on the same page when it comes to core compression.

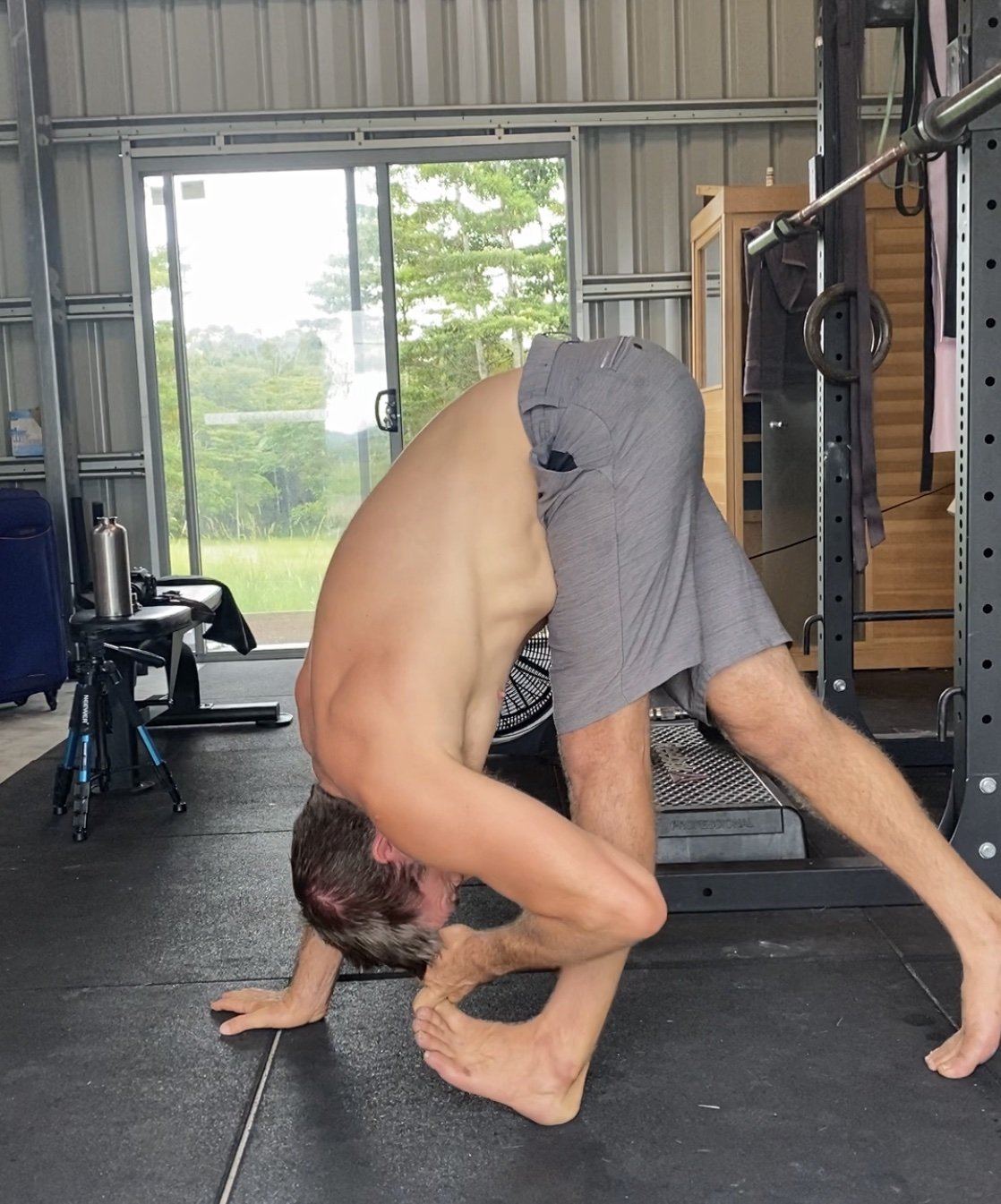

The best way to think about core compression strength is the closing of the angle between the torso and the legs—your ability to fold yourself in half.

This requires a certain level of posterior chain flexibility and a certain level of anterior chain strength.

Posterior chain flexibility is the ability to lengthen the muscles on the back of the body (calves, hamstrings, glutes, and back muscles).

Anterior chain strength is the ability to contract or shorten the muscles on the front of the body (shins, quads, deep hip flexors, and abdominals).

Therefore, core compression training is all about lengthening and strengthening so you can close the angle between your torso and thighs.

Benefits of Core Compression Training

Stability and Control: The core muscles, which include the abdominals, obliques, and lower back muscles, provide stability and control during movement.

A strong core helps us maintain proper body alignment, which is essential for mastering our body weight and unlocking gymnastics skills.

Balancing: A lot of gymnastics movements involve balance - pistols, squats, handstands, planche, gymnastics rings training, parallettes training, and more.

Core compression strength helps us maintain balance by stabilising the pelvis and ribcage to prevent unnecessary wobbling or shifting.

Flexion and Extension: Core compression strength allows us to achieve proper body positions, such as tuck, pike, and even arching.

These positions are essential for executing skills like l-sits, press to handstands, pistol squats, pikes, pancakes, and even the gymnastic bridge.

A strong core assists in controlling and maintaining these positions, leading to better performance and reduced risk of injury.

Tension: Gymnastics movements often require significant levels of tension. A strong core helps us generate this tension by providing a solid foundation from which tension and force can be efficiently transferred to the limbs.

Injury Prevention: A strong core supports the spine and helps maintain proper body alignment.

This can significantly reduce the risk of injuries, which are common in gymnastics due to the high levels of tension in the body and the repetitive nature of the sport.

Transitions and Skills: Many gymnastics skills involve transitioning between different body shapes quickly and smoothly. Core compression strength aids in these transitions, allowing us to move seamlessly from one shape to another.

Rings and Bars Work: On apparatus like the rings and bars, we must support our body weight while performing various swings, holds, and rotations. Core compression strength is essential for maintaining proper body alignment and controlling these complex movements.

Pikes, Pancakes, Tuck and L-sits: Core compression strength is particularly important for achieving the tuck and pike shapes, which are fundamental to many gymnastics skills.

In summary, core compression strength is a foundational element of gymnastics that facilitates stability, control, flexibility, power generation, and injury prevention. It enables gymnasts to execute skills with precision and grace, contributing to overall performance.

The Core Compression Journey

There are a lot of different ways to train core compression strength, and choosing the right method is essential to your success.

An adult who has tight hamstrings and weak core compression isn’t going to start their journey with movements like seated pike leg lifts or strict toes-to-bar. They don’t yet have the flexibility or strength to perform these movements effectively.

They need to stretch the posterior chain and strengthen the anterior chain before progressing to these more advanced movements.

Hence, we must find the most effective way to achieve this goal.

In a hanging, seated, or even a standing leg lift, the gravity vector and lever length increase the intensity of the leg lift.

For example, in a standing front scale, the gravity vector pushes the leg down towards the floor and opposes the contraction of the core compression muscles.

As we lift the leg to be parallel to the floor, the lever length increases (the foot is further away from the body), which increases the load on the core compression muscles.

As we move closer to our end range, the intensity becomes harder. It’s also important to note we are also weaker at our end ranges.

Tight hamstrings also limit core compression strength because as the core compression muscles contract, the hamstring muscle must lengthen.

When the hamstrings are tight, the anterior chain muscles fight against them.

Gravity, leverage and posterior chain flexibility work against us in hanging seated and standing core compression exercises.

Hence, the best place to start is lying on the floor.

Supine leg lifts are the perfect starting place for adult gymnastic skill seekers who lack core compression strength and/or hamstring flexibility.

Unlike the hanging, seated and standing core compression variations, the supine leg lifts us gravity and leverage to our advantage.

When the leg is perpendicular to the floor, both gravity and leverage are neutral (zero).

Gravity and leverage assist the core compression gains as we move the leg past the perpendicular point. Both forces push the leg toward the torso and help close the angle.

What if you can’t lift the leg perpendicular to the floor?

This is where the bent-knee lift-offs can strengthen the core compression muscles.

By bending the knee, we lessen the hamstring flexibility demands. This allows us to strengthen the core compression muscles while using other exercises to stretch the hamstrings.

Once you have the strength and flexibility to hold the working leg past the perpendicular point, you’ll be ready to move on to more advanced core compression exercises.

This is when standing and hanging core compression exercises are recommended.

The range of motion available in standing and hanging core compression exercises is much greater than in seated core compressions.

If unable to hold straight legs parallel to the floor in hanging or standing variations, we can again shorten the lever length by bending the knees. Think hanging tuck-ups, for example.

Hanging strict toes-to-bar are even more challenging because the angle between the torso and thighs is closed further, requiring more strength and flexibility.

Seated variations, like seated pike leg lifts or l-sits on the floor, are significantly harder because they target the end-range of motion, the weakest point.

That's why seated leg raises are a far more advanced core compression exercise.

Armed with this knowledge, you're on your way to successfully developing core compression strength.

If you're an adult gymnastic skill seeker who wants to build core compression strength and forward fold flexibility, look no further.

Here is your chance to unlock core compression strength and forward fold flexibility with our FREE Core Compression Strength & Forward Fold Flexibility Program.