Health Posture PART 1: Gymnastics Bridge

“Movement Is life”… “No movement? No life!”

Your spine has roughly 50 joints that allow you to move in complex ways. Unfortunately, due to a sedentary lifestyle and lack of movement complexity, most of us have lost full control of our backbone. A healthy spine is a mobile spine, how often do you move yours?

As a quick nerdy side note, there is some really cool literature done by Thomas Myers that explains how muscles and connective tissues connect in patterns/chains and can link to common issues. In one of the chapters of his book Anatomy Trains, he describes a chain known as the Spiral Line.

When we train in the gym, most exercises are done with a neutral spine. Deadlifting, squatting, machines, dumbbells, etc. all promote strengthening the spine in a neutral plane. But what happens when we need to lift an awkward object like a couch or an atlas stone? Does a heavy load during spinal flexion, extension, rotation or side bending suddenly make you as weak as a butterfly? How often do you train out of alignment? Sport and life are not always performed with a neutral spine. We continue to train “in alignment” but we live “out of alignment.” Can you make any sense of this?

What is required to make a good gymnastic bridge?

The gymnastic bridge is a full body movement that takes our spine into extension. It requires strength and tremendous flexibility to hold. The more you have of both the easier this move and all the moves built on top of it will become. Ask a handful of people what area of the body contributes the most to a great gymnastics bridge shape, many would say lower back flexibility. The lower back or lumbar spine actually is an area that is primarily built for stability, and really shouldn’t be the primary method of extension for gymnasts bridging and many other movements.

Ideally, we should demonstrate an equal distribution of the mobility demand through the shoulders, lower back, and hips during a bridge. “Bridge mobility coupling” - the even distribution of mobility through the shoulders, lower back, and hips.

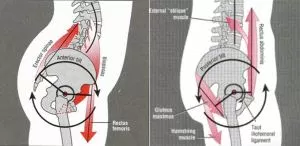

Lower back flexibility is often excessive (hypermobile) as a result of poor posture and limited range of motion in the thoracic and shoulders. Over time habit develops, and the athlete tends to bend/hinge from the lower back segments instead using the hips. The bridge itself is one of the best exercises to improve the flexibility in these areas.

What are some of the limitations that impact the bridge?

Shoulder stability, strength limitations, poor shoulder joint positioning, muscular imbalances, issues related to motor control, core stability, poor breathing patterns, and poor glute strength/control/usage are all issues that can impact the “construction” of a good gymnastics bridge.

The bridge is a great exercise for building shoulder and hip flexor flexibility which will help overhead movement such as the snatch, jerks, handstands, etc.. Due to the latissimus dorsi being crucial for gymnastics, athletes are usually very overdeveloped in this area. Athletes generally fail to stretch/mobilise the latissimus dorsi as often as the lower body and trunk. The pectoralis muscles also become tight because athletes typically overuse this muscle, but does not appropriately strengthen their middle back to counterbalance bad postural habits. This is why many athletes have the “rounded shoulders” look to them.

Pair overuse with under stretching and the athlete develops the imbalance of not being able to bring the arm overhead.

Limiting factors include:

Hip flexor mobility - unable to open the hips fully

Lack of shoulder flexion into hyper-flexion possible from tight and overdeveloped latissimus dorsi, pectoralis, biceps, and/or rotator cuff muscles.

Lack of thoracic extension (bending from the middle/upper spine)

Tight shoulder joint (internal and external rotation of the humerus)

Awareness and motor control of scapular position

Overhead stability issues (chronic "rounder shoulders" posture)

Thomas Myers outlines how flat feet or overpronation can be linked through other muscular connections to the pull on the structures of the front/side of the thigh, then possibly contributing to the pelvis to tilt forward (anterior pelvic tilt).

Why does the bridge matter?

Having restrictions in the hips and shoulders may cause the back to take all of the workloads when it shouldn’t. This is huge to realise and understand because it can possibly be how an athlete gets progressive back pain due to weightlifting, gymnastics, cycling, running, and other activities which can possibly lead to serious lower spine issues.

Repetitive overuse of the lower back at one or two segments may possibly lead to joint inflammation, muscular strains, tissue irritation, and ligamentous sprains. More dangerously, spine pathologies can develop where a vertebra slips forward in the spine (spondylolisthesis) causing pain and biomechanical mal-alignments. In more severe cases a piece of the vertebral bone gets fractured (spondylolysis). The most common site for many of these problems is the L4/L5 junction (very lower spine above buttocks), and many times this is the area athletes complain of pain. If the hip flexors and shoulders aren’t regularly mobilised they will not share the tension load, the lower spine will have to do all of the work and may possibly get injured.

When a back injury occurs from this scenario, many athletes become caught up in the common dilemma of who they should listen to. The doctor says they have to stop training, a coach wants them to keep practising as much as they can, parents get overwhelmed, the athlete’s lower back is screaming during practice, and they feel hopeless. Prevention is key.

Sometimes lower back pain can be a very complex beast to tackle. There are many other causative influences that can play a role such as core strength deficits, poor neuromuscular control during movement, repetitive high impact forces, postural habits, and the list goes on. Jumping straight into a gymnastics bridge is not the best idea, gradual progression is recommended. Steps need to be taken to increase mobility in the restricted areas first (hip flexor, anterior hip, shoulder, thoracic, etc…)

In Part 2 of this post we will look at some other issues that impact posture and sports performance.